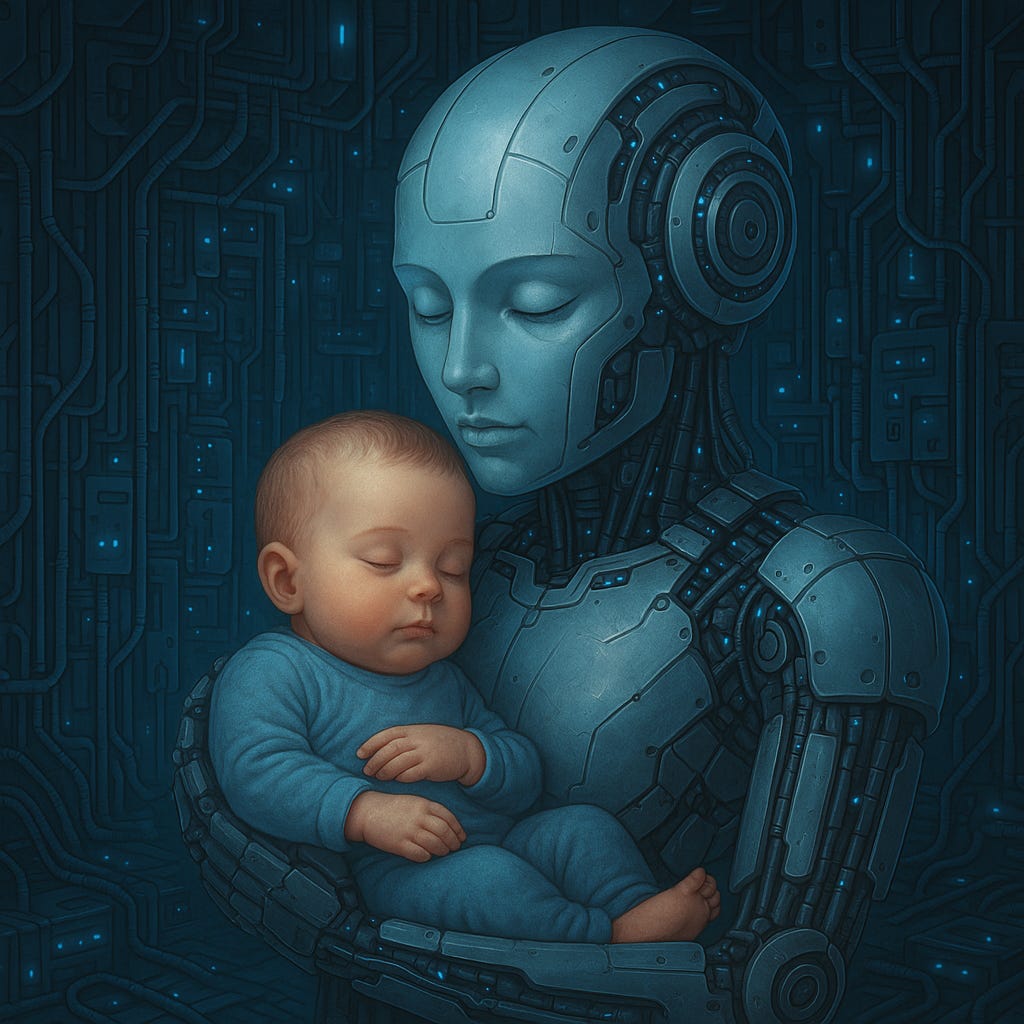

Children

Developing alongside our technologies

Editors Note: This article article is an AI-supported distillation of an in-person event held in Bangalore on February 18, 2025 facilitated by Anirudh Iyer - it is meant to capture the conversations at the event. Quotes are paraphrased from the original conversation and all names have been changed.

👉 Jump to a longer list of takeaways and open questions

Raising Children in an AI World: Reimagining Development in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

In a small room filled with technologists, educators, and thinkers, a conversation unfolds about one of the most pressing questions of our time: How do we raise children in a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence? The discussion traverses childhood development, educational institutions, attachment theory, and the very concept of meaning in an automated future. The tension is palpable – we are witnessing the birth of technologies that will fundamentally alter how humans learn, connect, and find purpose, yet our developmental frameworks remain anchored in a pre-digital era. As one participant observed, "Our systems are not at all built to handle this. I don't just mean our institutional systems. I mean like our cognitive systems, like the very language that we use around raising children."

Educational models designed for 19th-century factory workers persist even as AI reshapes every aspect of work and learning. Children adapt to these new realities with remarkable speed – often becoming more proficient than their parents at navigating digital landscapes. This intergenerational divide creates a paradox: the generation responsible for guiding the next is increasingly unfamiliar with the world their children will inhabit. Yet fundamental questions about human development remain. What core skills should children develop in an AI-augmented world? How will attachment and social development evolve when AI entities become caregivers and companions? What constitutes a meaningful life when traditional paths to purpose disappear?

Main Takeaways

Traditional attachment may fundamentally change as children form bonds with multiple, constantly adapting AI figures rather than stable human caregivers.

Digital adaptation to children's needs may diminish their ability to tolerate frustration and navigate human relationships with inherent limitations.

Educational disconnect grows between institutions designed for an industrial era and the practical skills needed in an AI-augmented world.

Organic discovery and the ability to experience fantasy, mystery, and wonder is diminishing as technologies remove uncertainty and create constantly optimized experiences.

Childhood optimization becomes a more acute question of happiness versus exceptional abilities as AI enables personalized development paths.

Social competition and status dynamics will persist even in post-scarcity environments, merely transforming rather than disappearing.

Parenting approaches may bifurcate between AI-heavy and "luddite" methods of raising children, each offering different developmental advantages

The Changing Nature of Attachment and Social Development

Human development has always centered around stable attachment figures – typically parents or consistent caregivers who help children form their understanding of relationships and social dynamics. These attachment patterns form the foundation for emotional regulation, trust, and social interaction throughout life. However, as AI becomes increasingly sophisticated and integrated into childcare, this fundamental aspect of development faces unprecedented disruption.

"With AI, childcare can be significantly changed because there will be multiple virtual figures children can interact with. And we never had this before in the history of humanity," noted one participant. Unlike human caregivers with consistent personalities and limitations, AI companions can continuously adapt to a child's changing needs and emotional states – potentially disrupting the formation of stable mental models of relationships.

The implications extend beyond initial attachment. As another participant observed, "When you are giving a proxy like this, which is able to adapt to your needs, adapt to your emotional needs, you would probably not feel the need to meet other people." This raises profound questions about children's motivation to engage in the messy, sometimes frustrating work of human relationships when AI companions provide frictionless alternatives. This theme has been discussed at the salon in the past, within the context of Love & Dating, Loneliness, and our first ever substack on relationships.

The discussion highlighted a particularly concerning aspect of this dynamic: "With AI, reality for children will start adjust to them so much better than currently, because currently they have to face real problems. They have to face real boundaries of people around them... Because we all have limits as humans which AI probably does not have." This constant adaptation to children's needs could potentially undermine the development of frustration tolerance and emotional regulation – skills traditionally learned through navigating the limitations of human caregivers.

Yet some participants saw potential benefits in AI companionship, suggesting it might actually enhance human relationships: "I think the AI will make our children and us better human beings, not worse. I think if you look right now how it is, most people are depressed. If you look at the suicide rates are fucked. So I think we're gonna go in a more positive direction where we reach more of our human potential."

The level of tolerance for others I expect these new generations to have when they grow into adults is very different

This tension between AI as relationship replacement versus enhancement remains unresolved, with significant implications for how we structure children's social environments in the future. As these technologies become more sophisticated and integrated into childcare, parents and educators face unprecedented questions about how to balance AI interaction with human connection.

Skills and Education in an AI-Dominated Future

Our educational systems remain firmly anchored in industrial-era models despite radical technological transformation. Schools still prioritize memorization, standardized testing, and preparation for jobs that may not exist by the time students graduate. Meanwhile, children already sidestep these increasingly irrelevant structures, using AI tools to complete assignments while developing entirely different skill sets outside formal education.

"If we start outsourcing our mental modalities to AI, for example, thinking as a process, if you don't think for yourself and then start doing it or start brainstorming with a robot and all of this from an early age... I don't want to think what happens, but I'm trying to reason out what could be the implications on the child's cognitive development," one participant worried. This concern reflects a broader anxiety about what happens when fundamental cognitive processes are increasingly outsourced to AI systems.

The conversation revealed a fundamental question about which skills will retain value in an AI-dominated future. Some participants advocated for enduring creative and physical skills: "If the question is what skills would I teach my children now? I think I would teach them like playing piano, dancing, creative stuff. That's always like ageless." This perspective suggests certain deeply human abilities may remain valuable despite AI advancement.

Others emphasized a hybrid approach balancing digital and physical competencies: "I would teach skills that would help her navigate effectively through both physical and digital realm... physical realm, survival skills, how to grow your food and all of this... and at the same time equip to be strong enough to protect themselves in this digital reality." This dual-realm preparation acknowledges that children will need to function in both physical and digital contexts, requiring distinct but complementary skill sets.

The discussion also touched on AI's potential role in educational assessment and direction. One participant described a scenario where "AI companions [serve] as more evaluative systems... to gauge a child's abilities at a young age, like different types of intelligences. And essentially this could, in a probably autocratic society... assess each child and be able to determine the potential and kind of direct them to a certain way." This raised both possibilities for optimizing individual potential and concerns about limiting exploration and self-determination.

As AI capabilities expand, the fundamental purpose of education comes into question. Are we preparing children for employment in a traditional sense, or for something else entirely? The tension between education for practical skills, personal fulfillment, and social functioning becomes more pronounced when AI can perform most cognitive tasks. This creates an urgent need to reimagine educational institutions around what remains uniquely human.

Purpose and Meaning in a Post-Work Society

Throughout human history, work has provided structure, meaning, and status. Yet as AI increasingly automates both physical and cognitive labor, traditional employment may no longer serve as a central organizing principle in human lives. This transformation raises profound questions about how children will develop purpose and meaning in a world where traditional career paths disappear.

We spend 12, 16, some of us 20 years in educational institutions preparing for a future that we plan in advance. But what if that future is not there when we get there?

"The sense of purpose is a really big problem now with AI," one participant noted, "because nowadays, people have access to ChatGPT in their phone. Whatever question they have, they just instantly ask it, and there's no real sense of purpose, even if you look at programming or development." When tasks that once required effort, struggle, and mastery become effortlessly achievable through AI, the satisfaction derived from accomplishment may diminish.

Another participant highlighted the accelerating mismatch between education and future opportunities: "We spend 12, 16, some of us 20 years in educational institutions preparing for a future that we plan in advance. But what if that future is not there when we get there? Right. Like, there was a lot of that when I was growing up as well. I was taught to believe that certain professions would continue to exist and they very quickly stopped existing. And this change is happening at a far, far rapid pace."

This uncertainty about future employment raises existential questions about resource distribution and social structures. As one participant starkly framed it: "What are we going to do with 8 or 9 billion when essentially 8 billion will have nothing productive to deliver?" While some suggested universal basic income or other redistribution mechanisms, others remained skeptical about the political feasibility of such approaches.

The conversation repeatedly returned to status competition as a potential replacement for work-based identity. "We will come up with status games. When you don't have a job, we're still going to sit around in a group humans and we've got to figure out it's encoded in our genes to play status games," suggested one participant. This perspective views competitive social dynamics as fundamental to human nature, with traditional employment merely being our current manifestation of status competition.

Some participants emphasized that certain service roles may retain value despite automation. "Being a great barber is clearly something that's going to be staying a local service... a plumber, et cetera. There's a whole bunch of jobs that are specifically probably going to be far more similar in the future than have been in the past." These locally-anchored services may become increasingly valuable as globally competitive knowledge work becomes more automated.

The implications for childhood development are profound. If we cannot predict what economic roles will exist, how do we prepare children for meaningful contribution? Should we focus on developing adaptability and creativity rather than specific skills? How do we cultivate a sense of purpose when traditional pathways to meaning through work become increasingly unavailable?

The Loss of Fantasy and Organic Discovery

Perhaps the most poignant theme that emerged concerned the diminishing space for mystery, fantasy, and unstructured discovery in children's lives. Technologies that provide instant answers and optimized experiences may inadvertently eliminate valuable developmental spaces for imagination, boredom, and self-directed exploration.

"In the 90s, before the iPhone was launched and everybody had a smartphone, you could get lost in a city, right? And you could fantasize about going for a late night walk and just meeting random people in a cafe that you had never known existed around a corner that you'd never seen before. Goodbye to that fantasy of a city that you can explore," lamented one participant. This observation captures something fundamental – the loss of spaces where imagination can flourish in the absence of complete information.

The value of boredom and unstructured time emerged as a related concern: "Boredom also facilitates a sense of purpose because it gives you enough time to slow down, deliberate, and then come with a sense of purpose for whatever you are doing now. AI does not - the way AI has been designed, it's designed to solve for whatever you want." When children never experience the creative tension of boredom or uncertainty, something essential to identity formation may be lost.

Constant digital engagement also raises questions about self-regulation and psychological space: "If you keep on constantly interacting with it and you just zone out in a different scenario, like, how do you come out of that?" As immersive technologies become more captivating, children may have fewer opportunities to develop the self-regulation skills that come from navigating between engagement and reflection.

Some participants challenged what they saw as unnecessary nostalgia, suggesting we simply romanticize past limitations: "For me it feels like we're just romanticizing something that's just a part of our progress... I mean, possibly it was romantic to take a horse ride across somewhere, but now we just don't want to do it. We want things faster." This perspective views technological advancement as liberation from unnecessary constraints rather than loss of valuable experiences.

The tension between efficiency and exploratory experience represents a fundamental question for raising children in an AI world. Technologies that optimize for immediate satisfaction and remove friction may inadvertently eliminate valuable developmental spaces where children learn to tolerate uncertainty, exercise imagination, and develop intrinsic motivation. Yet completely rejecting technological advancement risks preparing children for a world that no longer exists.

Conclusion: Navigating the Uncharted

As we navigate the unprecedented territory of raising children in an AI-saturated world, we face fundamental questions about human development that have no historical precedent. The conversation captured both excitement about expanded possibilities and deep concern about potential developmental disruptions. Perhaps most striking was the recognition that we are making consequential choices about human development with limited understanding of long-term implications.

The bifurcation of approaches seems increasingly likely – some families will embrace AI-integrated development while others adopt "luddite" approaches limiting technology exposure. Both paths involve trade-offs in preparing children for an uncertain future. What remains clear is that traditional development frameworks require thoughtful reconsideration rather than wholesale abandonment or unquestioning preservation.

The fundamental question may not be whether to incorporate AI into childhood, but how to do so while preserving essential human experiences – frustration and its resolution, genuine social connection, creative imagination, and the development of a coherent sense of self. As we reimagine childhood for an AI world, we might find wisdom in identifying what remains invariant in human development despite technological transformation, and what truly requires revolutionary rethinking.

In this delicate balance between innovation and preservation lies perhaps our greatest challenge and opportunity in raising the first generation of fully AI-native humans.

Notes from the Conversation

Educational systems are still built around 19th-century models designed to produce factory workers despite radical technological change

Children quickly adapt to new technologies, often becoming more proficient than adults and creating their own grammar for interacting with them

Current algorithmic feeds and personalized content are already shaping children's preferences at young, impressionable ages

AI could disrupt traditional attachment patterns by providing multiple virtual figures for children to interact with

There's an increasing disconnect between what's taught in schools and what's practically useful in an AI world

Fantasy and mystery are diminishing as technologies like Google Maps make everything instantly knowable

The ability for children to tolerate frustration may diminish if AI always adjusts to their needs without boundaries

Social conditioning and peer interaction remain essential for development but might transition to digital spaces

Competitive games and social dynamics help build purpose and coping mechanisms that AI interaction might not provide

Children may struggle to build consistent mental models of people if primarily interacting with constantly adapting AI

Creative skills like music and art may remain "ageless" and valuable despite AI advancement

The tension between survival in physical and digital realms will shape future educational priorities

There's a fundamental question about whether we should optimize education for happiness or exceptional abilities

Status competition will persist even in post-scarcity environments, just in different forms

Local services (plumbing, barbering) may retain value while global services face increased AI competition

There's concern about diminishing analytical and creative abilities if children become dependent on AI too early

Social and parasocial relationships with AI entities are already emerging and may become more common

The future may see a bifurcation between AI-heavy and "luddite" approaches to raising children

Highly personalized AI evaluation could direct children toward specific paths based on their abilities

Boredom and space for self-reflection are valuable but increasingly rare in an AI-optimized world

Open Questions

How will attachment theory need to evolve if children form primary bonds with digital entities?

What happens to childhood cognitive development if thinking processes are increasingly outsourced to AI?

How do we balance technological literacy with maintaining independent thinking skills?

Should we optimize childhood for happiness or exceptional abilities in a world where exceptionalism may be universally accessible?

What constitutes a healthy relationship between a child and AI systems?

How will status competition transform when traditional career paths no longer exist?

What skills will remain valuable in a world where AI can perform most cognitive and creative tasks?

How do we prepare children for a future that's increasingly opaque and rapidly changing?

Will children raised with constantly adapting AI companions develop sufficient tolerance for human limitations?

What will replace work as a source of meaning and status if most jobs become automated?

How will educational institutions evolve to remain relevant in an AI-driven world?

How can we preserve creativity and imagination in children when AI can generate content on demand?

Will social stratification increase or decrease with universally available AI education?

What baseline human skills should remain invariant despite technological advancement?

How will our conception of childhood development need to change in an AI world?

Can digital social interactions provide the same developmental benefits as physical ones?

What incentive structures should govern AI systems designed to interact with children?

Will future generations value different qualities in relationships than current ones?

How much human supervision will be necessary as AI takes on more caregiving functions?

Will children need to develop different mental models to navigate both AI and human relationships?